- PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules): Governs how programs and services handle authentication.

- Network Security Tools: Utilities such as iptables and Firewalld regulate access to network services.

- SSH (Secure Shell): Provides secure remote access over unsecured networks, with SSH hardening ensuring only authorized users can connect.

- SELinux: Enforces security policies to isolate applications running on the same system.

While numerous tools exist to secure a Linux system, this article focuses on basic access control, file ownership, and permissions.

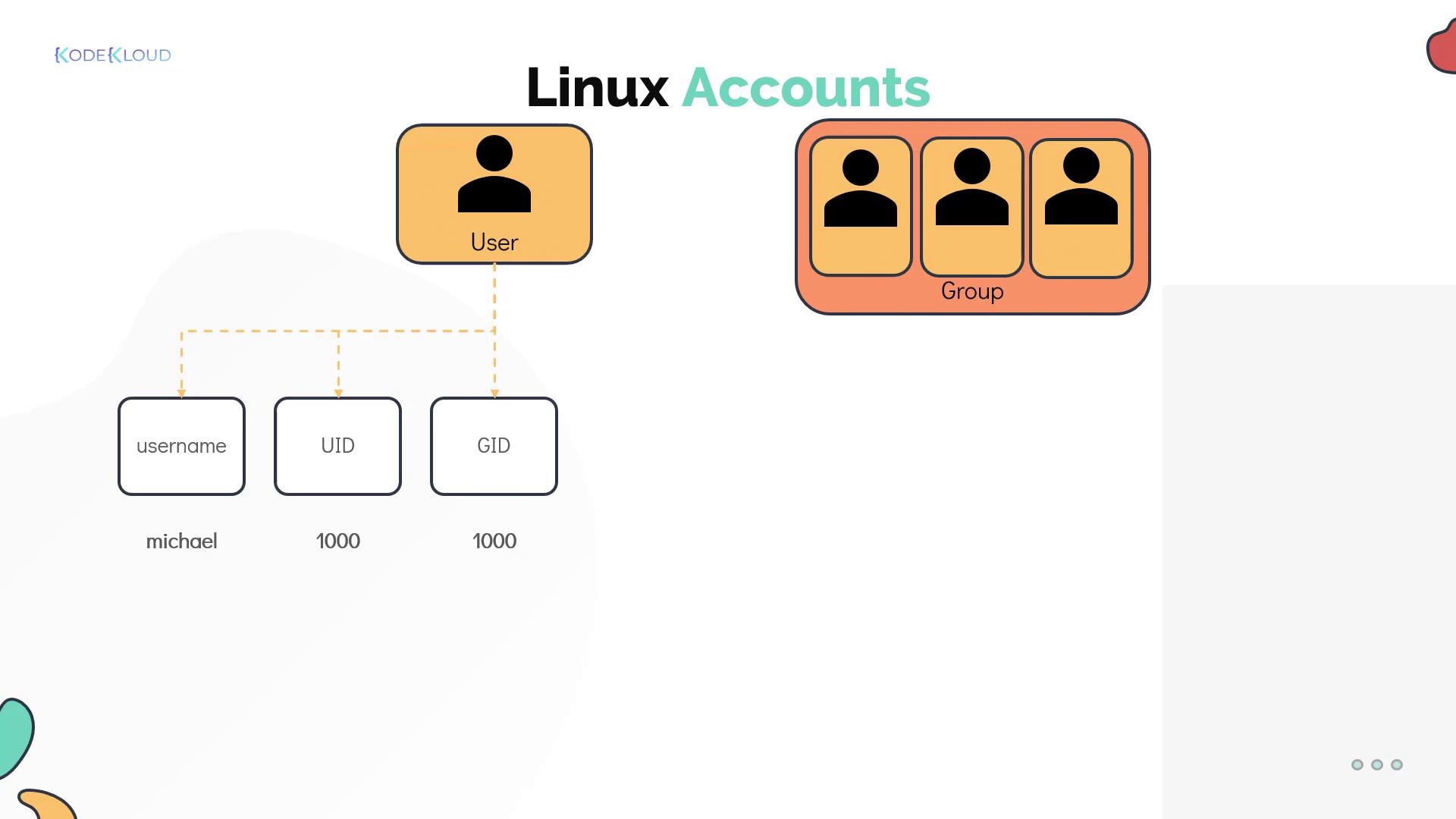

User and Group Accounts

What is a Linux Account?

Each Linux user is associated with an account that holds critical details such as the username, password, and a unique identifier (UID). Account details such as the home directory and default shell are stored in the/etc/passwd file. For example:

/etc/group file.

Example: Grouping Developers

Consider a scenario with two developers, Bob and Mumshad Mannambeth, working on the same system. They can be grouped under a Linux group called “developers” to facilitate shared access to particular files and directories. For instance:id command:

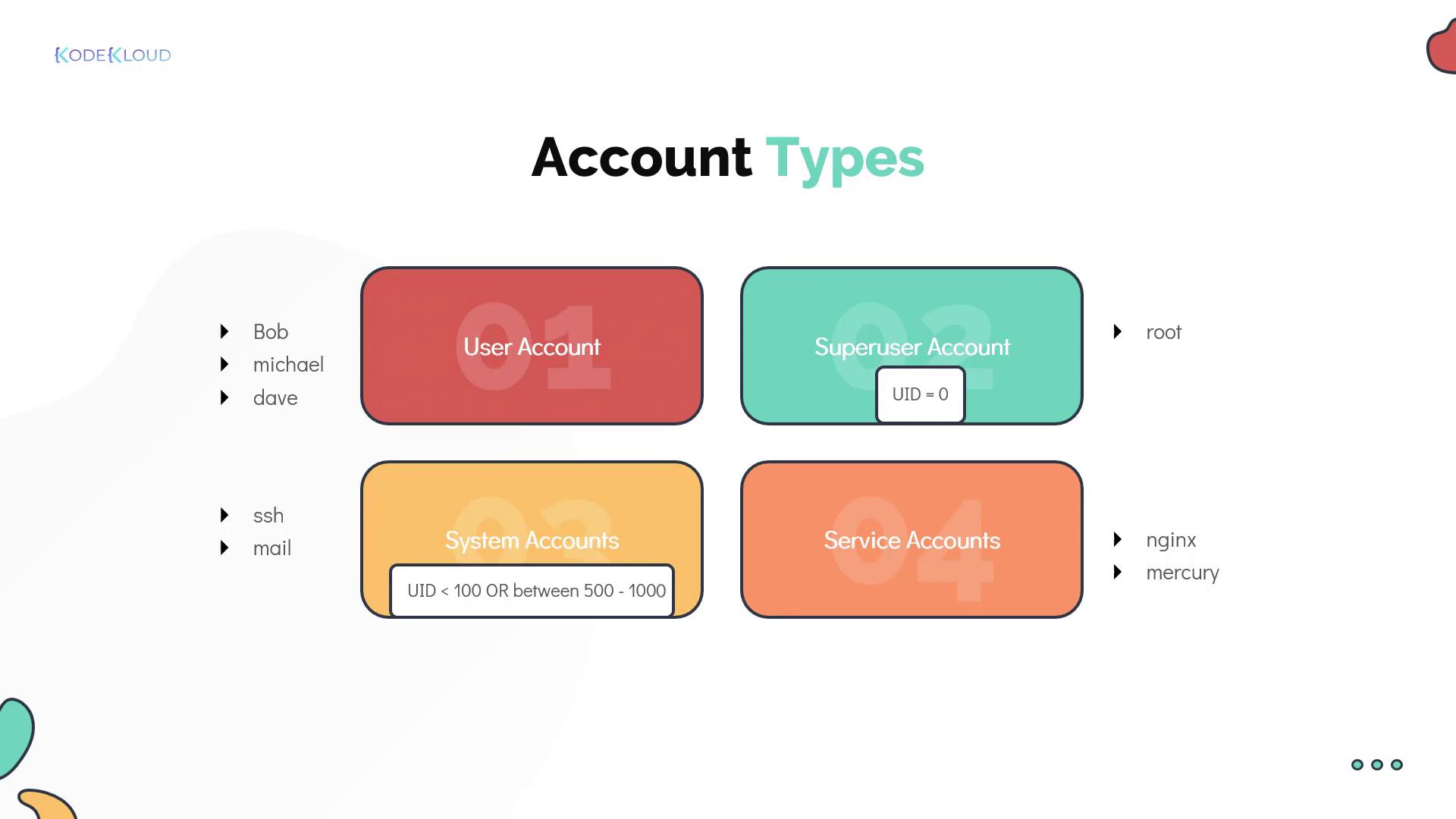

- Regular User Account: Represents an individual person requiring system access.

- Superuser Account: The root account (UID 0) with full system privileges.

- System Accounts: Created during OS installation for software and services; typically have UIDs under 100 (or between 500 and 1000) and usually lack dedicated home directories.

- Service Accounts: Similar to system accounts, these are created for specific services such as NGINX.

Switching Users and Privilege Escalation

Linux offers multiple methods for switching between users:Using the su Command

Thesu (substitute user) command enables you to switch to another user, including the root account. For example, to switch to root:

su -c (which requires the target user’s password):

su is a useful utility, it is generally recommended to use sudo for enhanced security.

Using the sudo Command

Thesudo command allows trusted users to execute administrative commands using their own password. This method avoids the need to log in as root directly. For example:

sudo configuration is defined in the /etc/sudoers file, where administrators can configure specific privileges. For example, Bob may have full administrative rights while Sarah might be restricted to rebooting the system only.

When using

sudo, ensure that only trusted users are granted access to prevent unauthorized system changes./etc/sudoers file:

Understanding the sudoers File

The sudoers file is organized as follows:- Lines beginning with a hash (#) are comments.

- The first field specifies the user or group (groups are prefixed with

%) that is granted sudo privileges. - The second field, typically set to

ALL, indicates on which hosts these privileges apply. - The third field, within parentheses, defines the users or groups the command can be executed as—usually set to

ALL. - The fourth field lists the allowed commands. This field can either be set to

ALLfor unrestricted access or limited to specific commands (e.g., permitting Sarah only to execute the reboot command).

In summary, mastering Linux accounts, groups, and user switching methodologies is essential for securing your Linux system. By understanding file ownership, permissions, and privilege escalation, you can implement robust access control measures that safeguard your environment. For more insights into Linux security and administration: